Why visit Odisha?

Despite having travelled all around India, I have always been reluctant to visit Odisha, the state overlooking the Bay of Bengal, located along the east coast of the sub-continent. A primitive and less well-known part of India, where tribes carry outancient animist rituals and use archaic methods of land cultivation.

The painting bought in Kolkata

What helped me decide this year was a painting bought in an art gallery in Kolkata a couple of years ago. I look at it every day, hanging in my dining room in Milan. It portrays a woman in a forest, wearing numerous metal rings around her neck, with a shamanic gaze. An intriguing and mysterious image. True or false? Touristy or authentic?

The villageholic, as my friends define me, doesn’t give up this year. Odisha is mine! Besides trying to understand how these primitive indigenous tribes live (there are around sixty of them, called Adivasis, that have inhabited the area for thousands of years), I am looking forward to seeing beautiful Hindu temples, unlike all the others.

Luck is on my side

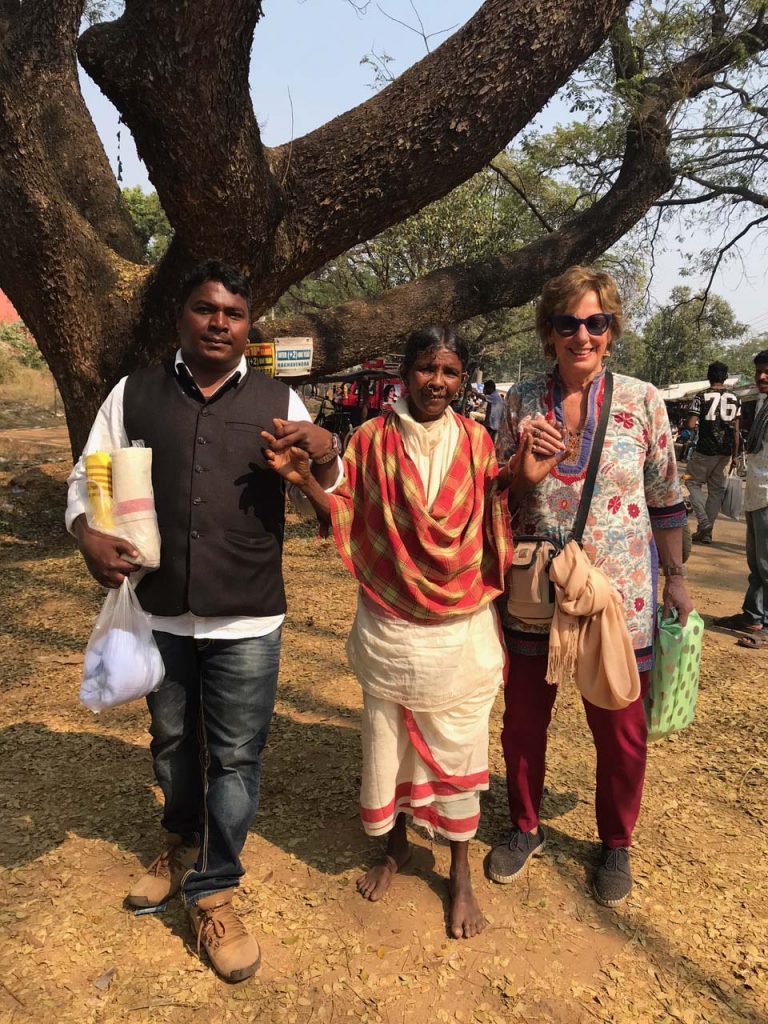

Jitu, who is going to accompany us on this trip, is a leader of the Dongria Kondh, a clan in the Niyamgiri hills, an area covered by dense forests, deep gorges and impetuous streams. He speaks English well, thanks to a missionary who turned up in his village and who convinced his parents to send him to school in Bhubaneshwar, the capital of the state of Odisha.

Jitu is proud of his tribe. He wouldn’t leave his native village for anything in the world. “To be a Dongria Kondh”, he explains, “means growing rice in these fertile valleys, harvesting the produce, such as pineapples, jackfruits, mangoes, sweet papayas, ginger and oranges, but above all, it means venerating the mountain god, Niyam Raja.

Without Niyamgiri, the sacred mountain and our god, there is no life for us”. The triangle, which symbolises the mountain, can be seen in all their art and craft, as for example, in the shawls that girls embroider before their marriage. They like to embroider together, and in fact this is how I saw them in Chatikona, sitting in the shade of the trees in the garden of the Dongria Karodh development agency.

This small community that is defying the government and trying to resist the big

multinational companies is worthy of admiration.

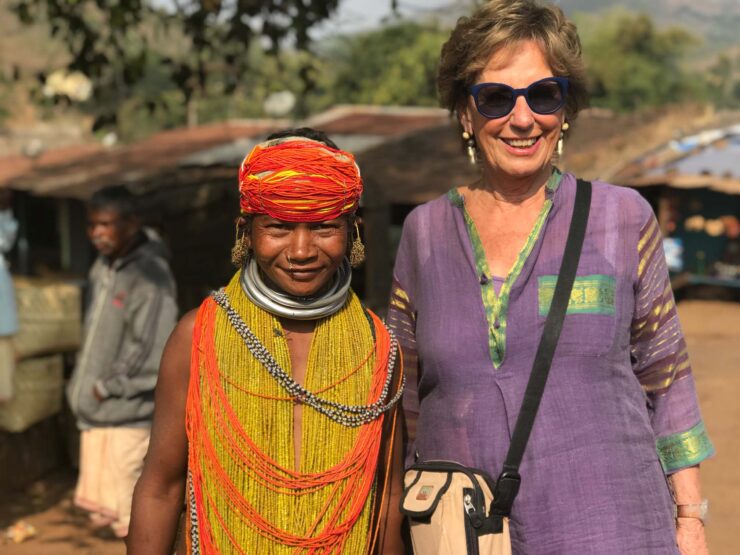

- Dongria Kondh woman

- Using banana leaves as a plate

- Sarees at Chatikona market

- Dongria Kondh villagers in Chatikona

- A village on the plains

- Portrait of a Bonda woman

- Bonda villagers arrive at the Onkadelli market

- Bonda villagers at the Onkadelli market

- Cows leave the Mali Dhoulir Ambo village

- Onkadelli market

- Cultivated fields

In 2013, in the name of their sacred mountain, 8000 members of the Dongria Kondh tribe, belonging to 12 villages, won a heroic battle against the mining giant, Vedanta Resources, who intended to mine bauxite worth 2 billion dollars in their hills. “They wanted to take away our soul”, Jitu points out. The company was planning to create an open-pit mine which would have diverted the course of the rivers and marked the end of the Dongria Kondh population. In 2013 the Supreme Court recognised the Dongria Kondh’s right to decide whether mining should be carried out in the mountain. Theiranswer was “NO”.

Jitu loves to tell us about life in his village. They are up at five in the morning to work in the fields when it isn’t too hot, without omitting a short break in the company of friends to drink sago-palm juice, gathered from the forest’s giant palm trees, an alcoholic beverage that provides energy for the long excursions in the forest. “It is part of our traditions”, he explains. “though one mustn’t exaggerate”. He adds, “Instead of tea, we drink sago-palm juice”.

At the Onkadelli market

Their customs are rather free and very different from those of the Hindus. Jitu tells us that girls over 13 years of age sleep with a group of around ten friends in houses built to accommodate them. At night they are visited by boys from the neighbouring villages. They make friends and learn to stay together before getting married. As far as marriage is concerned, the most surprising fact is that the wife has to be a few years older than her husband, so that she can be taken care of in her old age!

Jitu is a cheerful person. Like the Dongria Kondh, for that matter.

On our way back to the hotel in Semilguda, the sound of drums attracts us like the sorceress Circe. We enter the village of Takirigumma and are welcomed with open arms. There is a wedding underway. The women dance in a circle, their arms intertwined behind their backs. I accept their invitation and join the dance. Sago-palm juice goes around and everyone is merry…A bit of alcohol won’t hurt.

Dongria Kondh woman

On Wednesday at the Chatikona market

A government law restricts trips to hill villages, but it is possible to meet Dongria Kondh villagers on Wednesdays at the Chatikona market, attended even by people who come here by train from neighbouring villages. Jitu’s friends descend from the hills by bicycle or in small jeeps loaded with people and goods to sell. The place bustles with activity. The women wear coloured flowers in their hair, which is looped around a sort of cloth tube andembellished by many hairpins. They remind me of hairstyles in the Thirties. All have necklaces around their necks, many earrings, and three rings through their noses, while boys only wear two. On their heads a bamboo basket in which to place the purchased products. Wrapped around their bodies, a simple hand-woven cotton saree with a coloured border. I like these sarees a lot and buy a few to make shirts for the summer.

- Young Dongria Kondh women

- Village on the plains

- Dongria Kondh cultivated fields

- Reaching the market by jeep

- Village basket-weavers

- Village drum players

- The countryside at dusk

- How can you not buy this woman’s necklaces?

Villages on the plain can be visited. In one, baskets are woven, in another work is being done with a lathe… In our honour, young boys play the drums, the children dance happily and the women stand in the shade of the thatched roofs that extend towards the ground forming a kind of porch, while along the banks of the inevitable watercourse, mothers wash their children.

Finally a close encounter with the tribe of the woman portrayed in the painting at home. Business is business…

They are the Bonda people, more reserved and austere than the Dongria Kondh; they are very short and are known as the naked people. When we meet them for the first time at the weekly Thursday market, in Onkadelli, we are stunned. Legend has it that Sita, the wife of Lord Rama, offended because she was laughed at by some Bonda women while she was bathing in a river, condemned them to cut their hair and to go around with scanty clothing. It is for this reason that Bonda women cover their shorn heads with beads and their body with infinitely long yellow and orange bead necklaces. Jitu explains to us that the metal rings around their necks help to protect them from being attacked by forest animals. You just can’t help but take pictures. The colours and faces are unforgettable. I am not surprised if they ask to be paid for taking photographs. After all, I could even make money selling them…Business is business.

Bonda woman at the Onkadelli market

A picnic among the yellow mustard flowers

Unexpected and very pleasant. We climb over a wooden fence and find ourselves among fields of rice, cauliflower and peas in Guneipada. We look around. The women are working, the men tending the animals. We sit in the shade of a wide tree with our picnic basket enjoying the peace of the countryside and the sound of water flowing in the streams..No multinational has the right to occupy this territory!

Picnic in Guneipada village

The first part of this trip, dedicated to the Adivasis, ends with this pastoral scene. We then descend towards the coast into a totally different world, the India of Hindu temples. I will tell you about it in the next instalment.